How to groom a West Highland white terrier

Excerpt from Donatella Diana's book "West Highland white terrier" ISBN 884123007X

Drawing 1 shows the appearance-typical of a West Highland White Terrier arriving at its first stripping (between 6 and 3 months) without having known adequate grooming beforehand (this may also be a Westie previously groomed but never again followed until the next session by the groomer). It is obvious that from these conditions one cannot, in good conscience, plan an exhibition program until after at least three months of constant, methodical work (provided that the bangs do not undergo severe “depletion” during the stripping phases, due to drastic interventions on incurably felted areas). A professional groomer, however, does not often have show subjects in front of him: he is therefore much more frequently confronted with cases of restoring a “look” that conforms to the breed standard. I hope that the photos and drawings that follow will also, and especially, come in handy for non-professional Westie owners; for that reason I will try to explain clearly even what will seem obvious or trivial to the most learned.

Drawing 2 shows the trimming (right) of a previously set dog (left). However, it is premature to talk about trimming: this operation consists of maintaining the standard image by the constant replacement of hairs as they mature and by conditioning the coat worked by stripping at regular intervals, which accentuates its thickening (keeping the undercoat under tight control) but prevents its disordered growth. The first substantial check to be made is to decide whether or not our pet has enough typical hair texture such that it can be stripped without the latter representing unnecessary violence; silky curly or cottony hair are defects that stripping cannot help to heal, and the damage that is done to the skin, the time that a good job requires and, not least, the unsatisfactory final appearance fortunately discourage even the most ardent fans of the stripping knife. A good quality coat, even when damaged by drug abuse, hasty (shear) grooming or frequent bathing (these are, in general, the agents that can change the structure of the hair), presents itself with a more or less dense and more or less ‘open’ surface layer of bristly, rough, hard, ‘goat-like’ hair (in the best subjects it is even of the consistency of bristles, but it is unfortunately those subjects that struggle to produce fringe or ‘furnishings’). The skin is protected by a dense layer of down, called undercoat, which is soft, velvety to the touch, vaguely greasy, compact and significantly shorter than the length of mature hair. Mature hair is defined as hair that has completed its growth cycle and already has the ‘replacement’ developing in the hair follicle. Let us summarize the concept with an example: a stripping dog is like a forest planted with shrubs. The shrubs are the fur, the underbrush is the undercoat: a good balance is one that helps the various elements interact with each other for mutual interests. So there are definite rules: do not touch the sprouting shrubs; do not deplete the soil or alter its factors; do not clear forest prematurely because the undergrowth protects the roots of trees that are still young and will downsize itself due to lack of light and nutrients as soon as the stems become stronger. The undercoat, however, must be kept under

control at stripping because its development is immediate and haphazard in many, many Westies. In addition, the undercoat significantly slows the emergence of new hair to the surface, so that it is profitable to vigorously ‘slough’ the dog’s entire body after about 45 days from the date of stripping, using a small knife with dense, fairly deep teeth for the purpose (caution: scrape ‘towards’ and tilting the knife towards yourself; if used perpendicular to the animal’s body, you would run the risk of injuring the skin).

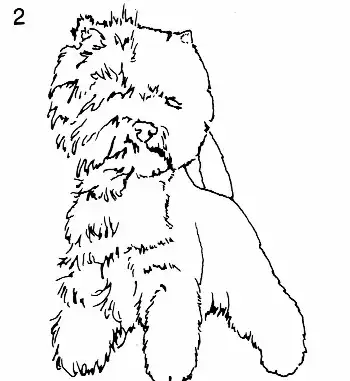

Drawing 3 shows the growth and trend directions of the hair and undercoat: they are the same ones to follow when stripping or trimming (or even shearing). It is important to know the directions and trend of the hair even simply when brushing because the coat has thermal, insulating and protective functions only if it is respected and its integrity is preserved. Knowing how to brush your Westie is the first important step to overcome to ascend to the sublime heights of the sculptural preparation of the show dog. I am of the opinion, although not very widespread, that a dog, to be fully enjoyed, must always (or almost always) show itself in top form. How can, therefore, a Westie owner who has already experienced stripping (or shearing when the hair does not lend itself) leave it completely messy in the months following the grooming and waiting for a new appointment?

In the photo we see some of the most useful tools in grooming. From the top (left): the first two combs are equivalent in validity (the first has slightly wider teeth than the second), both are made of steel, with blunt tips and wide and dense teeth; the length of the tooth, technically, is 7/8. The third comb, commonly called “flea comb”, has very fine teeth, is made of steel and has shorter teeth than the previous ones: it is very useful used as a rake on the undercoat to eliminate excess. There is a fourth (overlapping the scissors box): it is made of plastic, with a steel tail and is optional. It is the back lombing comb, its use is limited to the head of the Westie. In the box we see a pair of straight scissors: in the trimming of the Westie by stripping the use of straight scissors is limited to finishing the ears and feet (including foot pads). Next to the box is a ‘knot cutter’: essential, especially on fringes, on subjects that have been felted for a long time. Further down (far right): oval nailed brush (pin brush). It is a ‘gentle’ brush, with rounded tips (but without ‘balls’!) and long teeth. It is an alternative to the carder on rough hair and is more functional on fringes. Below (right): the knob (Terrier Palm): like the Pin Brush it is made of nails with a blunt tip (but shorter); the adjustable strap allows it to be adapted to the hand of the person working on the dog by grooming or rubbing the hair on the back as it grows back. Below (center and left): a series of stripping knives of various models.

Drawing 9 shows how stripping, blending and trimming can also be done by hand (plucking). This does not involve more professionalism but only more patience. Sometimes, however, plucking may be necessary in areas of the body with deteriorated or mistreated (shear-worked) hair

to recover particularly elastic and tenacious hair that, by resisting stripping too much, would risk being cut by the knife.

Drawing 8 shows the action of the carder and the correct position to have the Westie assume to reach with the brush all those areas where rain, dirt and other things contribute to the formation of felts. The dotted lines emphasize the areas that, if neglected by the brush (and the comb), become felted more easily.

The nail needs to be cut (or trimmed) if, when articulating the foot, it exceeds the normal size (or is curved) coming into contact with the ground. The dewclaws (the fifth toe of the front limb, which is often amputated at birth) must be trimmed at regular intervals because they can grow by twisting until they become ingrown (ring-shaped), thus becoming extremely difficult to treat and painful for the dog. It is preferable to trim nails that grow quickly and long often rather than subjecting a dog that is not used to this stress rarely and more radically.

Drawing 10 shows the final appearance of a Westie seen from behind. Note how the different lengths blend into a harmonious whole, especially between the shoulder and the plumb line (foreleg) and, at the height of the ribs, between the flanks and the ‘skirt’.

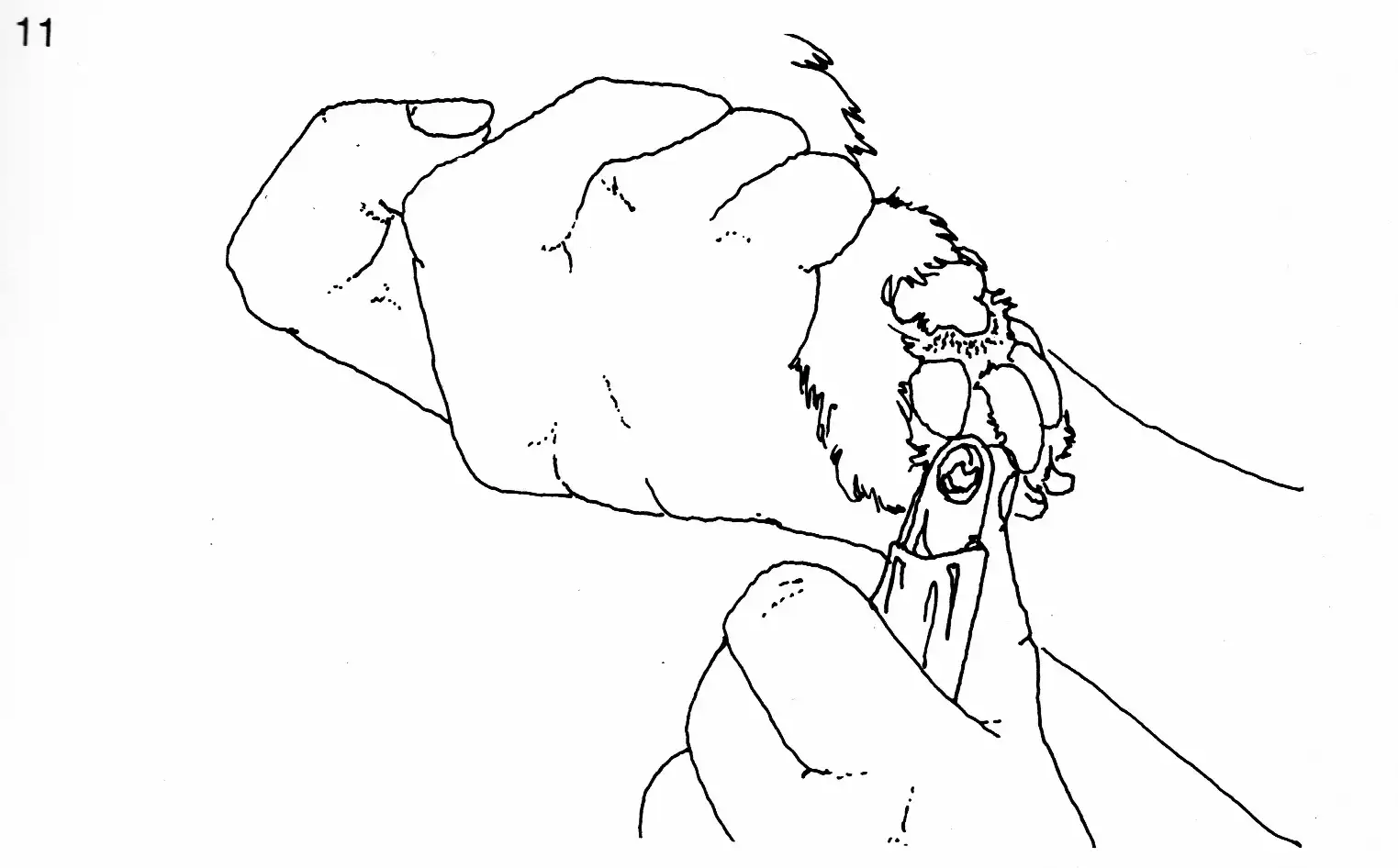

Drawings 11 and 12 exemplify nail cutting performed with ‘guillotine’ nail clippers. First of all it is essential to immobilize the limb ensuring the dog a fairly natural position, such as not to further upset the animal already quite tense in itself as it generally does not tolerate this practice well.

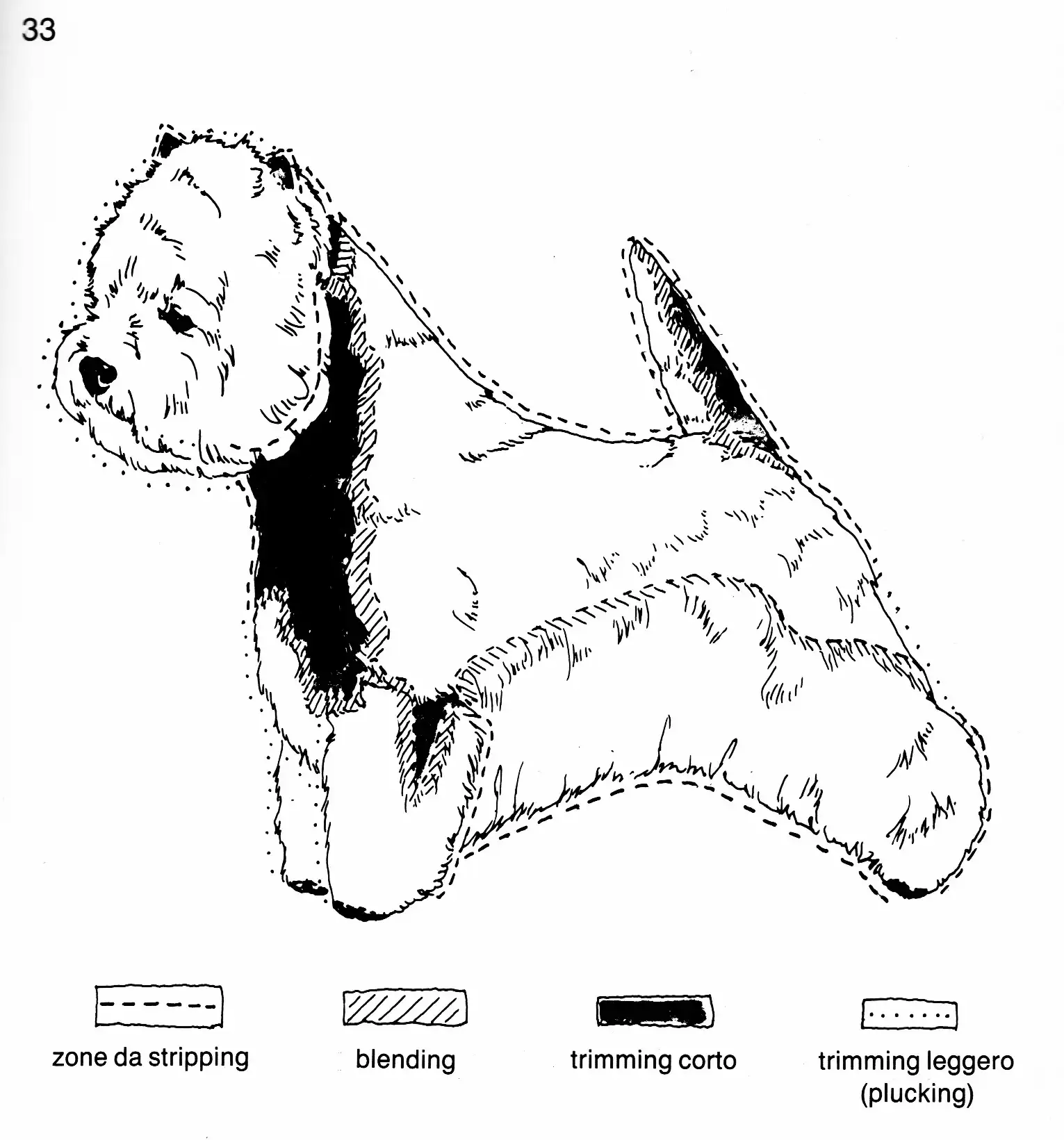

Drawing 33 shows a ‘hair’ subject, i.e. in ideal trimming conditions, a ‘ring’ Westie should be covered, along the topline and in all stripping areas, by a minimum of 3cm of hair, with maximum tips of 5-6cm (at the withers, buttock).